Nicolas, rum aficionado for over twenty years, is constantly looking to broaden his rum culture by tasting, studying its history, techniques and pretty much anything to do with his favourite spirit. This led him to write his own blog (cœur de chauffe), but also write for others, and more recently to import some of his absolute favourites, always with this idea of sharing his passion.

Nicolas, rum aficionado for over twenty years, is constantly looking to broaden his rum culture by tasting, studying its history, techniques and pretty much anything to do with his favourite spirit. This led him to write his own blog (cœur de chauffe), but also write for others, and more recently to import some of his absolute favourites, always with this idea of sharing his passion.

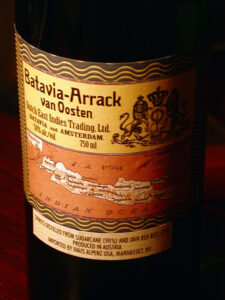

Indonesia, and more specifically the island of Java, is home to and produces a totally unique sugarcane spirit. Its name comes from Batavia, the former capital of the Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta), and from Araq, a word from the early days of distillation in the Middle East. This word means “sweat” or “condensation” in Arabic. It allows us to imagine the discovery of the first drops of distillate flowing from a still (al ‘inbïq).

Although relatively unknown today, it was widely appreciated and even considered superior to Caribbean rums during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe. The sailors were its best ambassadors, they claimed that it made the best punch.

It was mainly produced by the Chinese cane planters and sugar producers settled on the island. They had a thousand-year-old mastery of distillation. This is still true today, as families of Chinese origin still run the industry.

Arrack in the broadest sense of the word has been known for a long time in South and South-East Asia. It is made from palm sap, coconut or sugar cane. But it was the famous Batavia Arrack from Java, first recorded in the mid-1600s, that made its mark and crossed borders.

The Vereenigde Oost Indische, the Dutch East India Company, had a monopoly on the trade of this spirit in Europe. The now-famous Dutch rum brokers were primarily large traders of Batavia Arrack. This is the case of E&A Scheer in Amsterdam, for example: born in 1712, the company devoted itself almost exclusively to Batavia Arrack until the end of the 19th century. From that time onwards, rum replaced the Java spirit, whose historical turmoil considerably slowed down the race.

The Vereenigde Oost Indische, the Dutch East India Company, had a monopoly on the trade of this spirit in Europe. The now-famous Dutch rum brokers were primarily large traders of Batavia Arrack. This is the case of E&A Scheer in Amsterdam, for example: born in 1712, the company devoted itself almost exclusively to Batavia Arrack until the end of the 19th century. From that time onwards, rum replaced the Java spirit, whose historical turmoil considerably slowed down the race.

The making of Batavia Arrack

Batavia Arrack could be summarised as an Indonesian rum, but that would not be entirely correct. It uses very specific and fundamentally Asian methods. The major difference with rum is in the method of fermentation:

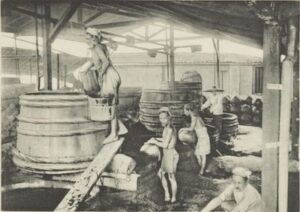

Sugar cane molasses, water and, above all, a red rice leaven are used to prepare the mash that is then distilled. Contrary to popular belief, this is not a variety of red rice with special yeasts. It is rather a rice fermented with a type of mold called “Koji” in the Japanese Shochu world or “Qu” in Chinese Baiju.

Sugar cane molasses, water and, above all, a red rice leaven are used to prepare the mash that is then distilled. Contrary to popular belief, this is not a variety of red rice with special yeasts. It is rather a rice fermented with a type of mold called “Koji” in the Japanese Shochu world or “Qu” in Chinese Baiju.

This mushroom is grown on steamed rice or simply soaked in water, for 3 to 6 days at room temperature. It is the monascus purpureus that gives the famous red colour to the rice by colonising it. It is also an ideal support for wild yeasts which develop abundantly. They thus ensure good control of the molasses fermentation which takes place in open-air wooden vats.

The distillation is traditionally done in an iron still. Today however, some Batavia Arracks are lighter, with less rice in the fermentation and a column still distillation.

In the past, it was lightly aged on the ships that brought it to the old continent. They were shipped onboard in large teak casks of 680 litres. It was then transferred to teak vats, in order to respect its aromatic profile. The Dutch merchants have kept these vats to this day.

Its aromatic concentration means that it is used in rum blends. It is also in the food, perfume and tobacco industries, and more generally in the flavouring industry. Its presence is discreet on the cane brandy scene, but we can be pleased that such a traditional and authentic spirit is still with us.