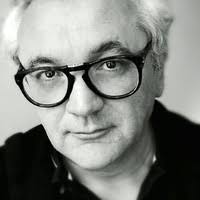

Jean-Pierre Saccani is a journalist. He was also editor in chief for many print media.

Liqueurs have made a great come-back thanks to the mixology trend, this specific segment in the world of spirits still cultivates its difference based upon its ancestral raw material and production techniques.

Outdated, liqueur was for quite a long time nicknamed «granny’s herbal tea», no comment… But thanks to a few bearded tattooed talented trendy hipsters and their mixology trend, they made it out from purgatory, somewhat of an Eldorado amongst the most influential representatives hold a similar status to that of a Michelin star chef… New distilleries have sprouted throughout the country, making the most of this niche by showcasing French terroir. Forgotten labels thus find a new lease of life, such as the famous Noyau de Poissy (an apricot kernels’ liqueur) revived/relaunched by Jean-Pierre Cointreau, owner of Frapin cognacs, Gosset champagne and Védrenne.

If the liqueurs market experienced a long slump in the 60’s & 70’s, these past few years it has been growing constantly by maintaining a strong regional presence. In an era of globalisation, this positioning sometimes turns out to be a real strength, as demonstrated by the success of Izarra in the USA where the powerful Basque diaspora’s favourite liqueur is to be found in just about any cocktails bar… Another advantage : liqueur also represents a certain form of naturalness, a prized value in these times when environment is a major focus . Fruits, plants, herbs, roots, barks, a list by no means comprehensive but in any case, raw materials which are sure to evoke nature!

If the liqueurs market experienced a long slump in the 60’s & 70’s, these past few years it has been growing constantly by maintaining a strong regional presence. In an era of globalisation, this positioning sometimes turns out to be a real strength, as demonstrated by the success of Izarra in the USA where the powerful Basque diaspora’s favourite liqueur is to be found in just about any cocktails bar… Another advantage : liqueur also represents a certain form of naturalness, a prized value in these times when environment is a major focus . Fruits, plants, herbs, roots, barks, a list by no means comprehensive but in any case, raw materials which are sure to evoke nature!

In order to become an alcoholic beverage, these raw materials are added to neutral alcohol or pre distilled as grain whisky, gin, vodka, etc. Liqueurs get their richness from aromatic parameters, the aromas extraction method remains essential. Two major techniques are used : distillation and infusion/maceration. The first requires the use of copper pot stills. The second means infusing fruits or plants in water before allowing them to macerate in alcohol during a few weeks in order to capture the aromas the most faithfully possible. Each type is then distilled on its own before the final blend. Last but not least, a liqueur must have an ABV between 15 à 55 % and contain, as per French regulation, at least 100 grams of sugar per litre, unlike its sister, the cream liqueur, which must contain at least 250 grams. A challenge when health authorities are issuing warnings against sugar!

Don’t over do it!

The amateurs recognise two great families amongst liqueurs: plant liqueurs some of which are truly worth noticing for their complexity, such as the Chartreuse (in the finest monastic tradition) and fruit liqueurs such as Cointreau, Guignolet, Grand Marnier… Fruit liqueurs are less and less used on their own but have made a great come-back in cocktails. To provide a comprehensive overview of the world of liqueurs, one must add spirits made from cream liqueurs, whether it be coffee, chocolate, flowers, whisky, anis seed or dried fruit such as almonds which are used to make Amaretto. And let’s not forget the fruits cream liqueurs and their typical syrupy texture which blends so well in white wine or champagne.

The amateurs recognise two great families amongst liqueurs: plant liqueurs some of which are truly worth noticing for their complexity, such as the Chartreuse (in the finest monastic tradition) and fruit liqueurs such as Cointreau, Guignolet, Grand Marnier… Fruit liqueurs are less and less used on their own but have made a great come-back in cocktails. To provide a comprehensive overview of the world of liqueurs, one must add spirits made from cream liqueurs, whether it be coffee, chocolate, flowers, whisky, anis seed or dried fruit such as almonds which are used to make Amaretto. And let’s not forget the fruits cream liqueurs and their typical syrupy texture which blends so well in white wine or champagne.

This diversity perfectly summarises this spirit’s capacity for resilience, undermined by their competition, whisky for instance, dismissed liqueurs as outdated/old-fashioned. Also pressured by modernity’s thirst for change and quick write off the past in order to make place for the future. Today, we are to say that liqueur is doing very well, making the most of its « vintage » quality. Like Proust’s madeleine, liqueurs have a rosy future ahead, just as long as they don’t overdo it, that is.