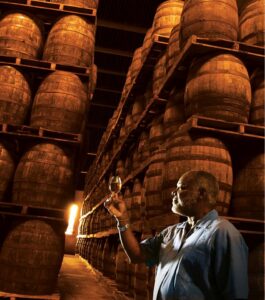

Alexandre Bernard, Rum expert and brand ambassador for Compagnie des Indes rums.

Rum has its roots in the Caribbean and South America. European settlers created this spirit. Since the introduction of sugar cane in the West Indies by Christopher Columbus, the cultivation of sugar cane and therefore the production of rum has grown. In a context of triangular trade, rum, along with sugar, was exported mainly to Europe and the United States.

In the middle of the 17th century, the colonists (mainly the Dutch) planted sugar cane in Guyana. The Netherlands have the first sugar exports recorded in 1661. Rum began to be produced by a few sugar factories and by 1670, most Guyanese factories were producing rum from molasses. The aim was to optimise the use of the residues from sugar production. Demerara rums were born at that time, and were exported massively in bulk. It should be noted that at the end of the 18th century, the Dutch ceded Guyana to the British, and the molasses were then also exported to countries such as Barbados. The so-called heavy Demerara rums became the basis for blends with lighter rums to supply merchants and the British Navy. The distinctiveness and diversity of Demerara rums, many of which are distilled in wood and copper stills, will contribute to the success of these nectars.

In the middle of the 17th century, the colonists (mainly the Dutch) planted sugar cane in Guyana. The Netherlands have the first sugar exports recorded in 1661. Rum began to be produced by a few sugar factories and by 1670, most Guyanese factories were producing rum from molasses. The aim was to optimise the use of the residues from sugar production. Demerara rums were born at that time, and were exported massively in bulk. It should be noted that at the end of the 18th century, the Dutch ceded Guyana to the British, and the molasses were then also exported to countries such as Barbados. The so-called heavy Demerara rums became the basis for blends with lighter rums to supply merchants and the British Navy. The distinctiveness and diversity of Demerara rums, many of which are distilled in wood and copper stills, will contribute to the success of these nectars.

At that time the insalubrity was disastrous. The sailors’ rations consisted mainly of biscuits and meat preserved in salt. The drinks consisted of water and beer stored in wooden barrels. These rations quickly became unfit for consumption (stagnation, algae growth). As a result, dehydration during these long voyages and then fever and scurvy decimated the crews.

After the conquest of Jamaica, where rum was abundant, William Penn gradually decided to substitute it for beer. In 1731, the Navy officially recognised the use of a daily ration of half a pint (275 ml) per sailor.

This ration, called “tot”, is gradually diluted. Sugar and limes are also added to provide nutrients and vitamins to the limey (nickname of the English sailors). In 1810, the London-based E D and F Man finalised the final version of the blend, which was approved by the English Admiralty. Pot still rums from Guyana were blended with strong rums from Jamaica and light rums from Trinidad and Barbados

The merchants were extremely powerful at that time, until the first half of the 20th century. Their lobby forbade distilleries in Barbados for instance to bottle under their own brand and to sell directly to consumers. A real golden age for bulk rum. This golden age came to an end in 1970 following Black Tot Day, as modern wars no longer required such supplies of alcohol.

As a great fan of the British tradition of bulk rum, Compagnie des Indes was one of the first to pay tribute to it with its Caribbean and Latino blends, and above all, with its Jamaican Navy Strength!

It was in the 18th century that the growing demand for rum, coupled with improvements in quality (distillation techniques, continuous distillation stills) and the development of trade routes, fuelled the interest of merchants. These merchants, mainly based in England and the Netherlands, transported these rums in bulk. They were then used to make blends.

In the Netherlands, it is the Batavia Arrack that is behind the success of the bulk rum trade. This Batavia Arrack is produced on the island of Java in Indonesia. It is a molasses base into which malted red rice yeast is added before being distilled. Batavia Arrack is then exported and aged for an average of 6 years in the Netherlands before being bottled. More recently, China and Sweden have favoured bulk trade. In the 19th century, Batavia Arrack was used in Swedish Punsh, the forerunner of cocktails, where it was combined with spices, sugar, water and citrus fruits, and consumed hot.

The Compagnie des Indes participated, on its own scale, in the discovery of this unique rum by being the very first to release a single cask bottling of Batavia Arrack in 2015. It is also included it in the Tricorne blend (up to 5%).

In France, and therefore in the West Indies, the quality of rum was not achieved until the beginning of the 18th century (mainly in Martinique) thanks to the work of Père Labat and the improvements he made in “repasse” distillation. This modernisation work and the boom in consumption (and therefore exports to the French mainland) propelled Martinique to the rank of the world’s leading producer at the end of the 19th century. It was even ahead of Jamaica, which was 10 times its size and had a much more advanced rum culture at the time!

In France, and therefore in the West Indies, the quality of rum was not achieved until the beginning of the 18th century (mainly in Martinique) thanks to the work of Père Labat and the improvements he made in “repasse” distillation. This modernisation work and the boom in consumption (and therefore exports to the French mainland) propelled Martinique to the rank of the world’s leading producer at the end of the 19th century. It was even ahead of Jamaica, which was 10 times its size and had a much more advanced rum culture at the time!

Phylloxera, a disease that affected French vines in 1863, caused problems with the supply of wine and was an unprecedented boon for the West Indies and the export of bulk rum. The shortage of Cognac and Armagnac allowed companies specialising in the rum trade, such as Bardinet in Bordeaux, to make the West Indies’ bulk rum flourish. This flourishing economy was further accelerated during the First World War as the needs of the army, both for soldiers and the arsenal, intensified.

This prosperity lasted until 1922, when the French distillers in metropolitan France had a quota law passed. This law limited the quantity of rum exported. The situation became catastrophic with the capitulation of France to Germany during the Second World War. After the war, the bulk market did not take off again due to the return of cheap metropolitan spirits, but also to the rise of whisky and the winter consumption of rum.

Nowadays, rum from the West Indies is (with the exception of the traditional rums from Reunion Island for rhums arranges (flavoured rums), or the Grand Arome for cooking) very little is exported in bulk. Problems with the yield of the cane harvest and the shortage of old juice due to growing demand make producers cautious.

Nowadays, if most distilleries prefer to keep their own distillate for their own bottling, bottlers are changing the situation. The great number of independent bottlers following the success of Plantation, Berry Bros, Compagnie des Indes, Vélier, etc. is a godsend for these companies. They sell them their surplus production directly and thus generate cash more quickly. The future looks more complicated. Increasingly premium consumption and speculation encourage the well-known distilleries to keep their juice to themselves. Especially as some markets with high purchasing power have not yet experienced the current craze we’re living on the old continent. These trends towards craft and premiumisation may limit bulk sales in the future.