Nicolas, rum aficionado for over twenty years, is constantly looking to broaden his rum culture by tasting, studying its history, techniques and pretty much anything to do with his favourite spirit. This led him to write his own blog (cœur de chauffe), but also write for others, and more recently to import some of his absolute favourites, always with this idea of sharing his passion.

Nicolas, rum aficionado for over twenty years, is constantly looking to broaden his rum culture by tasting, studying its history, techniques and pretty much anything to do with his favourite spirit. This led him to write his own blog (cœur de chauffe), but also write for others, and more recently to import some of his absolute favourites, always with this idea of sharing his passion.

A good distillate is a must to obtain a good spirit, the question is whether ageing is not just equally as important.

A master blender first determines what he wants to achieve with the ageing process. Is it to flavour the spirit by extracting the compounds contained in the wood? Or is it to oxygenate it, to give it a patina with time and evaporation?

It is often both of these results that are sought simultaneously, although this sometimes requires several manipulations.

A new oak barrel will give all the aromas and tannins it can hold. It is usually used during the first few years of ageing, as extraction is at a maximum and the woody character soon becomes predominant. This is reflected in the bright colour of the spirit.

A new oak barrel will give all the aromas and tannins it can hold. It is usually used during the first few years of ageing, as extraction is at a maximum and the woody character soon becomes predominant. This is reflected in the bright colour of the spirit.

Used casks are the ones most often encountered. They have already developed a patina, often from another spirit, and much of their tannin has already been “rinsed out”. They are therefore suitable for longer maturation, favouring oxidation.

In the world of rum, old bourbon (American oak) casks are the norm, and are also present in the majority of whisky. As bourbon can only be aged in new barrels, there is a huge market for used bourbon barrels, which other distilleries around the world benefit from.

In France, especially in Cognac, used French oak casks are called “fûts roux”. They have only contained Cognac, and often replace the new casks for the second part of the ageing process.

It is therefore not uncommon for spirits to pass through several types of casks. They can also be the result of the blending of several types of casks, whether they are new (extraction), used once (extraction + oxidation) or used multiple times (oxidation). It is therefore up to the master blender to sculpt the aromatic profile of his spirit, by juggling the different types of casks he has at his disposal.

What happens in the barrel ?

Ageing is a matter of chemistry that makes the spirit evolve, flavours it, softens it, colours it, until it is almost totally transformed. The type of wood used, its various treatments and its age are all criteria that interact with the spirit over time.

The two main families of oak used in spirits are American oak and French oak. French oak is known for the elegance of its fine grain and tannins, as well as for its subtle vanilla notes. American oak brings more sweetness, mild spicy and coconut notes.

These characteristics are more or less pronounced depending on how toasted they are. Indeed, coopers burn the inside of the barrel more or less intensely, in order to develop a certain aromatic profile. A light toasting develops notes of sweet spices, which will evolve into nutty aromas with a stronger toasting, to end up on the register of torrefaction with the charring of the barrel surface.

The latter also provides greater access to the heart of the wood, as it cracks on the surface, as well as a charcoal that filters out impurities from the spirits.

Barrel chemistry

Wood contains several elements that influence the flavour profile of the spirit, which the cooper and cellar master work with.

Wood contains several elements that influence the flavour profile of the spirit, which the cooper and cellar master work with.

The tannins, for example, provide a certain bitterness. This is largely washed out during the preparation of the wood. But the remaining tannins provide liveliness to the spirit and melt into fruity notes over time.

Lignin is a polymer which, when heated, develops aromas ranging from vanilla to smoke, depending on the intensity of the burning.

Lactones, derived from wood lipids, provide the typical coconut flavours of American oak, as well as woody and vegetal nuances.

Hemicellulose is a type of glucose, which gives the spirit a round texture and caramelises when the wood is heated. It is thus responsible for the amber colour, but also for the delicious notes of maple syrup or cooked sugar.

All these contributions from the cask come down to what is called extraction. It is more or less important depending on the previous uses of the cask, i.e. whether it is a new cask or a cask that has already contained other eaux-de-vie.

The size of the cask is also important, as it determines the contact surface between the liquid and the wood. For example, bourbon barrels have a capacity of 180 to 220 litres, whereas cognac barrels usually contain 400 litres.

We can also talk about the degree of barelling of the spirit, because the higher it is, the more the alcohol will extract the chemical elements from the wood.

The complexity of ageing

The other crucial phenomenon that develops during barrel ageing is oxidation, which leads to esterification, resulting from the meeting over time between the alcohol, the fatty acids in the spirit and oxygen. This is what develops additional aromas, and therefore complexity.

The other crucial phenomenon that develops during barrel ageing is oxidation, which leads to esterification, resulting from the meeting over time between the alcohol, the fatty acids in the spirit and oxygen. This is what develops additional aromas, and therefore complexity.

The aromas can also come from the alcohol previously contained in the cask. Indeed, used casks, whether bourbon, cognac or sherry, are often used to release the aromas accumulated in the wood during previous ageing.

It is this phenomenon that is mainly sought in the “finish” technique. Some casks are very marked by the alcohol they have contained, such as calvados, peated whisky or wine casks. The aim of the finish is to bring an additional nuance to the spirit, by offering it an additional maturation of several months in one of these casks.

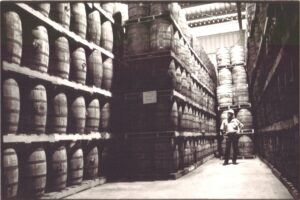

Finally, extraction or oxidation takes place in different ways depending on the environment in which the casks are stored. Evaporation (“the angels’ share“), and therefore extraction, concentration, but also oxygenation, are different depending on the temperatures in the cellar, their amplitude, and the humidity level. And it gets even more complicated when you know that all this varies within the same cellar!

Ageing is therefore a complex and fascinating process, which masterblenders aspire to master as best they can in order to obtain the desired aromatic profiles, and above all to meet the great challenge of maintaining them year after year.